In the last chapter, we chose our tools. We laid the foundation with Firebase and Google Cloud—a powerful, serverless architecture that gave us security, scalability, and speed. But a foundation, no matter how strong, is just a patch of concrete. The real work—the architecture—was about to begin.

This is the phase I call "From Concept to Skeleton." It's the most critical, most difficult, and most rewarding part of any new project. It’s where you are forced to translate the fuzzy, passionate "why" of your idea into the cold, hard, logical "what" and "how" of a system.

It's the digital equivalent of drawing the blueprint for a house. Before you can hammer a single nail, you must know where the walls go. You must decide where the load-bearing beams are, where the plumbing will run, and how people will walk from one room to another.

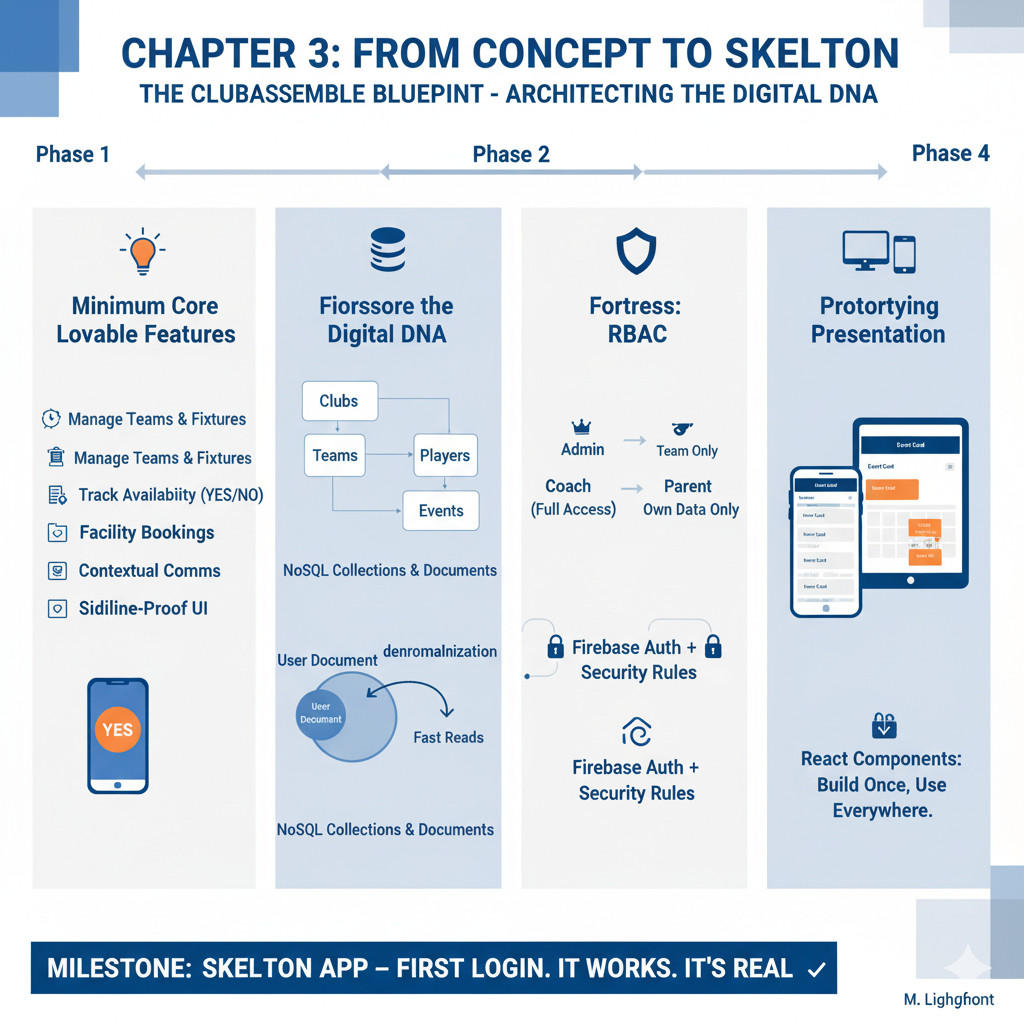

For ClubAssemble, this stage was all about laying that groundwork: defining the core features, shaping our data's DNA, validating our security model to be a fortress, and sketching the "feel" of the app that would one day live on thousands of phones.

Phase 1: Taming the Beast of Ambition (Defining the Core)

The first exercise was deceptively simple. I sat down with a virtual whiteboard and wrote down everything we wanted the platform to do.

This is a dangerous moment for any project. It’s the "feature creep" phase, where a simple idea can balloon into an undeliverable monster. The wishlist was a mile long: AI-powered coaching analysis, dynamic ticket pricing for club socials, integrated merchandise shops, live-streaming of U9s matches...

As a tech leader, I know this is the first great test: the battle of Ambition vs. Focus.

To win, you must be ruthless. We had to distill years of lived club experience—the sideline frustrations, the WhatsApp chaos, the spreadsheet archaeology—into a core set of non-negotiables. We needed to define the Minimum Viable Product (MVP).

I prefer to call it the Minimum Lovable Product. "Viable" isn't enough. It can't just work; it has to solve the problem so well that our first users—the coaches, the parents, the club secretaries—would love it.

So, we filtered the wishlist against one question: "Does this directly solve the 'admin quicksand' problem?"

If the answer was "no," it was cut. What remained was the heart of ClubAssemble.

- The Roster & Schedule: The ability to create a club, define its teams (U12s, Ladies 1st XI), and add members to those teams. This is the "who." Then, create events (fixtures, training) and link them to those teams. This is the "what" and "where."

- The "Availability" Button: This was the killer feature. The antidote to the WhatsApp chaos. A simple, unambiguous way for a parent or player to tap "Yes," "No," or "Maybe" for an upcoming event. This single feature was the cornerstone of the entire product.

- The "Facilities" Grid: The ability for an admin to define the club's bookable assets (Pitch 1, The Clubhouse, Training Nets) and their time slots. This was the spreadsheet-killer, designed to end double-bookings.

- Contextual Comms: Not just another chat app. That would be adding to the noise. I was adamant about this: communication had to be targeted. The goal wasn't "chat"; it was "clarity." The system needed to allow a coach to message only the "Unconfirmed" players for Saturday's match.

- The "Sideline-Proof" UI: This wasn't a feature, but a design principle. The interface had to be usable by a coach with one thumb, in the pouring rain, while holding a coffee. It had to be equally clear for a parent in their car or a club admin at their desktop.

That was it. That was the core. Everything else was noise. This focused "lovable" product was our North Star, and it gave us the clarity to move to the next, most complex step.

Phase 2: Architecting the Digital DNA (Mapping the Data)

With the features defined, the next question was: what data do we need, and how does it connect?

This is the data model. It's the most abstract, invisible, and permanent part of the application. It is the literal DNA of the system. If you get this wrong, you don't just refactor code; you have to perform open-heart surgery on the live application.

In the last chapter, I explained why we chose Firestore (a NoSQL database). Now, I had to live with that choice. A traditional SQL-minded engineer would think in rigid tables: a users table, a teams table, and a team_players_link table. To find a player, you'd have to "JOIN" all three. This is slow, rigid, and complex.

Firestore thinks in "collections" and "documents." The best analogy is a filing cabinet.

- A Clubs collection is the main filing cabinet.

- A club_ABC document is a single file in that cabinet.

- Inside that club_ABC file, we create a Teams sub-collection (a yellow folder).

- Inside that folder is a team_U12 document.

- Inside that team_U12 document, we can store simple data (like

teamName: "The Avengers") AND create another Players sub-collection.

This "nested" structure is incredibly fast. When a coach for the U12s logs in, the app doesn't need to search the whole database. It just goes directly to: Clubs/club_ABC/Teams/team_U12. Everything it needs—roster, schedule, etc.—is right there.

But this leads to a critical decision called denormalization. It's a scary word, but it's the secret to NoSQL performance.

Example: A player, "Jane Doe," is on the U12s. Her main user profile is in the top-level Users/user_JaneDoe document. She's also listed as a player in the .../Teams/team_U12/Players/player_JaneDoe document.

This feels wrong at first. We're storing her name in two places! But this is the genius of it:

- When the U12s coach loads his team, he only reads that one team document. He doesn't need to search the entire Users collection. This is lightning fast and cheap.

- When Jane logs in, she only reads her

Users/user_JaneDoedocument, which we've also stamped with her team info (e.g.,teamName: "The Avengers"). She doesn't have to search the Teams collection. This is also lightning fast and cheap.

Prototyping this in Firebase was a dream. We could build these data structures, adjust them on the fly, and immediately see how the app would behave. We could ensure that even with 100 clubs and 10,000 users, the app would remain fast because the data model was designed for "reads," not for rigid, academic purity.

Phase 3: Building the Fortress (Validating the Security)

Security was a constant, paranoid thread through this entire stage. We were handling PII for minors. A data breach wasn't just a technical "bug"; it was an existential, trust-destroying catastrophe.

Here, we had to distinguish between two key concepts: Authentication (Authn) and Authorization (Authz).

- Authentication: "Who are you?" This was the "easy" part. Firebase Authentication handles this. A user logs in with an email/password, and Firebase gives them a "passport" (a secure token) that says, "Yes, this is Jane Doe."

- Authorization: "What are you allowed to do/see?" This is the hard part. Just because Jane Doe is authenticated, does that mean she can see the U14s' team sheet? Can she see another parent's phone number? Can she see the club's finances? No, no, and no.

This is where we built our Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) model.

We defined our core user "roles":

- Player/Parent: Can only see their own data, their linked child's data, and their own team's non-sensitive events.

- Coach/Captain: Can read/write data for only the teams they are assigned to.

- Club Admin: Can read/write everything for their specific club.

We then built a "test-driven security" model before we wrote a single feature. We used Firebase's security rules emulator to write tests that proved our "fortress" worked.

Test 1: The Nosy Parent.

Attempt: user_Parent_A tries to read user_Child_B's data.

Result: ACCESS DENIED.

Reason: Rule says "Allow read only if request.auth.uid is in the parents array of this document."

Test 2: The Ambitious Coach.

Attempt: user_Coach_U12 tries to edit the team_U14 fixture.

Result: ACCESS DENIED.

Reason: We used Firebase "Custom Claims." When a coach logs in, their token is "stamped" with role: 'coach', teamId: 'team_U12'. Our security rule says, "Allow write only if the user's teamId claim matches the teamId of the document."

Test 3: The Valid Admin.

Attempt: user_Admin_ABC tries to edit the team_U14 fixture.

Result: ACCESS GRANTED.

Reason: Rule says, "Allow read/write if user has role: 'admin' and their clubId claim matches the document's clubId."

This process was exhaustive. But by the end, we had a set of rules that were proven to be secure. We had built the digital guardrails. We knew the foundation was solid, which gave us the confidence to start building the "house" on top of it.

Phase 4: Finding the "Feel" (Prototyping the Presentation Layer)

While the backend data models and security rules were taking shape in the "engine room," we also began exploring the "bridge": how would ClubAssemble actually look and feel?

This is where we returned to our "Sideline-Proof UI" principle.

I've seen so many apps for this space that are just ugly, shrunk-down spreadsheets. They are "mobile-friendly" (meaning they work on a phone) but not "mobile-native" (meaning they aren't good on a phone).

I believe in "Context-First Design."

- Context 1: The Parent. It's 7:00 PM on a Tuesday. They are in the car. They just got a notification. They need to open the app, see the one piece of new information ("New event"), and take one action ("Tap 'Yes'"). They need a big, clear, simple button. They do not need to see the club's 5-year plan.

- Context 2: The Club Admin. It's 2:00 PM on a Wednesday. They are at their desktop. They are trying to book all 200 fixtures for the entire season. They need a data-dense grid. They need to see the whole picture.

The app had to serve both users, seamlessly.

After testing several approaches, we settled on React.js. The choice was obvious for one key reason: Components.

In React, you don't build "pages." You build "components." We built one EventCard component. This component is a single, self-contained block of code that knows how to display all the data for one event (time, location, opponent, availability status).

This is the "magic" of React:

- The Parent sees this

EventCardin a simple list on their "Dashboard" screen. - The Coach sees a list of these

EventCardcomponents on their "Team" screen. - The Admin sees these

EventCardcomponents inside the "Facilities Booking Grid."

It's the same component, re-used in different contexts. When we needed to update it (e.g., "Let's add a 'View Map' icon"), we updated it in one place, and it instantly updated everywhere.

This approach gives us two huge wins:

- Development Speed: We build features, not pages.

- User Experience Consistency: The app "feels" the same everywhere. An

EventCardalways looks and acts like anEventCard. This makes the app predictable, intuitive, and easy to learn.

The Milestone: The "Skeleton App" is Born

By the end of this phase—weeks of whiteboard sketches, data modeling, and prototype code—we had it.

We had what developers call a "skeleton app."

It wasn't "feature-complete." There was no paint on the walls, no electricity, no furniture. But the frame of the house was up. You could walk through it.

I created the first real user: admin@clubassemble.com. I logged in. I saw the admin dashboard. I clicked "Create Team." I made the "U12s." I clicked "Create Event." I made "First Match @ 10:00 AM."

I logged out.

My heart was pounding a bit. This was the real test.

I created a second user: parent@clubassemble.com. I logged in. The first test passed: I couldn't see the admin dashboard. The RBAC rules were working. I could see "First Match." I tapped the "Availability" button. I clicked "Yes."

I logged back in as the admin. I opened the event. I looked at the availability list.

parent@clubassemble.com: Yes.

It was the most beautiful "Yes" I'd ever seen. It wasn't just a database entry. It was the first, tangible proof. It was the first strike against the "admin quicksand."

Seeing that first end-to-end user journey, from admin to parent, from data creation to data consumption, was a true milestone. It wasn't just a concept anymore. It wasn't just a pile of code.

It felt real. And it confirmed that the path we were on—from architecture to design philosophy—was the right one. The skeleton was built. Now, it was time to add the muscle.